Abstract

The study investigates the predicated thematic structures in the English text and its Urdu translation. The first objective is to define the variations in the Urdu translation of English predicated thematic structures. The second objective is to define how the variations in Urdu translation affect the thematic progression. The data has been collected from the English novel Things Fall Apart by Achebe (1958) and its Urdu translation Bikharti Duniya by Ullah (1991). The UAM Corpus Tool has been used to annotate the data and to find predicated thematic structures and their thematic progression. The findings show that the Urdu translation of English predicated themes is ambiguous and misleading. The English predicated themes have been translated as Urdu unmarked and marked ideational themes. Such unmotivated displacement of themes affects thematic progression. There occur some variations in the thematic progression of translated Urdu themes.

Key Words

Thematic Predication, Thematic Progression, Corpus, English, Urdu

Introduction

Systemic Functional Linguistics considers a language functional. The structure of a language is important only to serve the function. In SFL, lexicogrammar deals with grammatical descriptions and different meanings of a language (Eggins, 2004). SFL emphasizes a dimension called metafunctions which consist of ideational, interpersonal, and textual components. The first metafunction refers to the ability of a language to construe human experience into experiential and logical categories. The second metafunction embodies the ability of a language to negotiate social roles and attitudes. The third metafunction discusses the ability of a language to maintain a thematic structure in discourse. A thematic structure is the element of a clause that conveys a message. In each clause, one element is given prominence i. e. ‘Theme.’There is one further resource that contributes to the organization of a clause as a message. This is the system of predicated themes that involves a particular combination of thematic and informational choices.

This study finds the answers to two questions: (1) what are the variations in the Urdu translation of English predicated thematic structures, and (2) how the variations affect the thematic progression of predicated thematic structures. The answers to these questions have been investigated in Achebe’s novel. He has used predicated themes of emphasis and contrast in his novel. Through these structures, he has expressed the feelings, emotions, and actions of his countrymen to explain that they are a civilized nation.

The present research is a theoretical addition to the studies of SFL. Some previous studies have discussed the material clause themes (e.g., Yaqub et al., 2017), the syntactic variations (e.g. Tahir, 2019), the contrastive analysis of thematic structures (e.g. Riaz, 2018), and the hypotactic and paratactic thematic relations (e.g. Yaqub & Shakir, 2019) in English and Urdu. But to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, the existing literature lacks a contrastive analysis of the English and the Urdu predicated thematic structures.

This study is structured as follows—the Section 2 reviews relevant literature. The Section 3 discusses the elements of predicated themes and the patterns of thematic progression in detail. The methodology of this research is given in Section 4. The findings and results are given in Section 5. Section 6 concludes by presenting the variations in the predicated thematic structures and thematic progression.

Literature Review

The current study reviews the literature on the contrastive analysis of predicated themes and thematic progression in English and some other languages. But there exists no relevant literature on the contrastive analysis of predicated themes and thematic progression in English and Urdu. In a contrastive study of English and French, Péry-Woodley (1989) analyzed English and French essays of students and found thematic predication in c’est-clefts structures of French parallel to it-clefts of English. With the extensive studies on it-clefts in English, the complementary contrastive studies of French clefts are rare (Katz, 2000). Another contrastive study of it-clefts and wh-clefts in English and Swedish texts were reported by Johansson (2002) in which he commented on the functional differences. A major grammatical difference was identified by Van Huffel (2007) in predicated themes from English and its translated Dutch fiction text. He commented that a few cases of theme predication is similar in English and Dutch texts, but English predicated structure takes singular verb with empty subject and plural complement, but Dutch predicated structure receives plural verb with empty subject and plural complement. Another research has been conducted for the analysis of thematic structures in Barack Obama’s press conference (Kuswoyo, 2016). In this particular research, the appearance of predicated themes, including it-clefts has been reported with other types of themes. Along with the studies on thematic predication, some other studies were reported to identify the general thematic progression. Sade (2007) examined the thematic progression in Christian tracts written in Nigeria and found simple linear and constant thematic progression patterns. Moreover, Sari (2009) explored psychological, grammatical, and logical subjects and their conflation and combination with one another in a declarative clause. Sujatna (2013) observed the thematic progression of Sundanese female writers and found them using simple and multiple thematic progression in terms of linear theme and constant theme and rheme. This is a unique study due to investigating the element of theme and their functions. Thematic structures have been treated in a contrastive manner by Munday (1998, 2000), Taboada (1995), McCabe (1999) McCabe, and Alonso Belmonte (2001). To assign thematic status to the process element has investigated by Arús Lavid and Moratón (2012), Lavid (2010) and Lavid Arús and Moratón (2010a).

Theoretical Foundation

Predicated Thematic

Structures

The

predicated thematic structures are specified as it-cleft sentences (Halliday, 1994), which

direct the receiver's attention to an emphasized news in a particular

information unit. It-cleft is used as an empty subject which allows a certain

element to become a theme (Baker, 1992).

It-cleft sentences involve a contrastive emphasis, and they are thematizing

structures (Thompson, 1996). They

contribute to an emphasis on feelings and actions. They are used to contrast

what is already said with what is important to be emphasized.

The

system of predicated thematic structure is associated with the organization of

the clause as a message (Halliday,

1967). It includes a grammatical structure in the form of a cleft

construction (Halliday,

1994) which conveys significant meanings. This grammatical structure

begins with ‘it-cleft’ (Prince, 1978),

‘it-theme (Young, 1980),

‘cleft construction’ (Huddleston,

1984), or ‘focusing it-sentence’ (Erdmann, 1990). According to the semantic

and functional value, cleft sentences are used for emphatic meanings. The cleft

sentence is divided into two parts i. e. the matrix clause starting with a

meaningless pronoun, a copula verb, a highlighted element, and an embedded

relative clause. Here, it is important to note that the pronoun it is a

dummy subject and is known as a cleft pronoun. The predicated thematic

structures can propose a double thematic analysis (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004). The

subsequent figure displays the double analysis of predicated thematic

structure. In (a), the cleft pronoun is an unmarked theme, and in (b),

the whole matrix clause is considered a predicated theme, and the whole

embedded clause is a rheme. Collins

(1991: 170) refers to version (b) as "metaphorical

analysis in which the superordinate clause is all thematic". Consider the

following example.

Table 1. Predicated Thematic Structure in English

|

English Predicated Thematic Structure |

|||||

|

|

It |

was |

her father |

who |

persuaded her to continue. |

|

a. |

Theme |

Rheme |

Theme |

Rheme |

|

|

b. |

Predicated theme |

Rheme |

|||

Version

(b) has been used to analyze the predicated thematic structures in English and

Urdu. Urdu is a pro-drop (Hasan, 1984) and SOV (head-final) (Butt & King, 2005) language that has free word order, unlike

English. The predicated thematic structures in Urdu do not begin with it-cleft

because Urdu lacks clefts. Urdu introduces the subordinating that-clause as an

extra posed clause starting with an expletive. The morpheme y?h ‘it’ is used as an expletive in Urdu (Raza & Ahmed, 2011) because the equivalent of expletive there

does not exist in Urdu (Butt & King, 2007). In English, the predicated

thematic structure involves a predicative formula i.e.

it + be + highlighted element + relative clause. In Urdu, the

demonstrative pronouns j?h ‘this’, vo ‘that’ are used as so-called

equivalents of it-cleft. These demonstrative pronouns are just referring

expressions (Schmidt, 1999) which emphasize their

following noun phrases. These demonstrative pronouns precede a copula and an

NP. They function as dummy cleft pronouns in the Urdu predicated thematic structure.

These pronouns fail to agree with their copula, and they move an NP from its

unmarked position to the marked position. Furthermore, due to lack of agreement

with the copula, cleft pronouns are no longer considered true pronominal

expressions. In this case, cleft pronouns become dummy and empty subjects.

The predicated thematic structure in Urdu also

incorporates an exclusive emphatic particle hi

‘very’ to emphasize its preceding NP. Such particle is used to exclude

something else which may not be expressed (Schmidt, 1999). Along with

emphasizing its preceding NP, this article can also precede its NP due to

flexibility of word order. This particle is also an optional element, but it

doubles the emphasis when it is used with cleft pronouns. The most interesting

point is that a clause initial NP can also become a predicated theme when this

NP corresponds to its copula verb.

The Urdu copula verbs are he

‘is’, he? ‘are’, hu? ‘am’, t?h? ‘was’, t?he ‘were’, t?hi ‘was’. Young (2014a) claims that copula is a traditional

grammatical term for verbs as 'helpers .'In Urdu, a construction with optional

and dummy cleft pronouns j?h ‘this’, vo 'that', and

a plural complement cannot have a singular verb. Similarly, a masculine

complement can have only masculine copula t?h? 'was', and a

feminine complement can have a feminine copula t?hi 'was'. It happens because Urdu

verbs are marked with tense, number, gender, and case (Schmidt, 1999). They determine the gender

and number of pronominal subjects, which are merely distal and proximal

elements (Schmidt, 1999). The Urdu

copulas appear after the predicated theme (NP), which is modified by a relative

clause. Furthermore, Urdu creates a

predicative formula i. e. cleft pronoun

(optional) + highlighted element +

exclusive emphatic particle (optional) + copular verb + relative clause. The

following examples given by Schmidt, 1999: 212) indicate the

predicated thematic structure in Urdu.

Table 2. Predicated Thematic Structures in Urdu

|

Urdu Predicated thematic Structures |

|||

|

Ahmed hi It… Ahmed |

he is |

??s ne Who |

h?me? roke r?kh?. delayed us. |

|

Ahmed hi It… Ahmed |

he is |

?o Who |

qil? d?ekhn? ??ht?? t?h?. wanted to see the fort. |

|

jeh Ahmed hi It… Ahmed |

he is |

??s ne who |

h?m ko roke r?kh?. delayed us. |

|

jehi Ahmed It… Ahmed |

he is |

??s ne who |

h?m ko

roke r?kh?. delayed us. |

|

Predicated theme |

Rheme |

||

Additionally, despite being a pro-drop

language, Urdu uses the third person pronouns j?h ‘this’ and vo ‘that’ as necessary

predicated themes. Actually, these pronouns are marked predicated themes which

convey new and contrastive information. And according to a fact, the Urdu

pronominal subject conveying new or contrastive information is never ellipsed

or dropped (Hasan, 1984). On the contrary, the

dropness affects so-called cleft pronouns, which are dropped due to contextual

requirements. Urdu accommodates the function of it-cleft according to its

contextual referring expressions. Such accommodation makes the writers

translate English predicated themes into Urdu easily.

Thematic Progression

The predicated thematic structures may be convertible to an information unit composed of two components: the first part is the theme and the second part is rheme (Halliday, 1985). In fact, the organization of predicated theme and rheme contributes to the thematic progression. The thematic progression develops the parameters for given and new information in the text and the context. It represents the text development (Grabe & Kaplan, 1996) and organizes the texts into a coherent form (Butt et al., 2000). Generally, there is a subject known as point of departure in any clause containing another element as rheme. Theme contains given information while new information falls within the rheme. But the opposite is also common because new information is signaled by the prosodic prominence (Downing, 2001). The same is not true to the predicated theme because it is always a marked theme carrying new information (Halliday, 1985), and it consists of fixed prosodic prominence.

Thematic progression specifies the information flow in theme-rheme structures. Initially, three patterns of thematic progression: (1) simple linear, (2) constant, and (3) derived hyperthematic, were presented by Danes (1974). Additionally, the new patterns: split theme and split rheme were added in the theory of thematic progression by McCabe (1999). In linear thematic progression, the rheme of the preceding clause shifts into the theme of the subsequent clause. The rheme conveys new information while the theme conveys given information. In constant thematic progression, the same constituents in first theme are continuously selected as the theme of following clauses. The continuous selection of the same theme implies the repetition of the given information in many clauses. In splitting progression, the theme of the first clause splits into two items. Each item is considered a thematic element in the subsequent clause. Likewise, the information of the first theme splits and flows down into the following themes in chunks. These patterns are identified with reference to the semantic relations, including identical wording (like personal pronouns), synonymous expressions, paraphrases, and semantic inferences.

Research Methodology

Research Method

The existing study has used a descriptive research method. The theme-rheme model of systemic functional linguistics has been used as a theoretical framework. It is said, "Theme involves three major systems: choice of type of theme, choice of marked or unmarked theme, and choice of predicated and not predicated theme” (Eggins, 2004:299). The choice of predicated theme is investigated through both qualitative and quantitative research methods. This study has also applied the framework of thematic progression i.e., simple linear theme, constant theme, split theme, and split rheme (McCabe, 1999). The peripheral themes which do not fit in any of the thematic progression patterns (McCabe, 1999) have also been investigated in this research.

Samples & Corpus Size

In this research, the unmotivated displacement of predicated themes and its effects on the thematic progression has been analyzed from the English text, Things Fall Apart (Achebe, 1958), containing approximately 50000 words and its Urdu text, Bikharti Duniya (Ullah, 1991) containing 55000 words.

Annotation Instrument

The selected texts were annotated according to the scheme of UAM Corpus Tool (O’Donnell, 2008). Being semi-automatic, the UAM Corpus Tool exports an annotation scheme for the framework of SFL, which served the objectives of the current study. The following scheme shows multiple-level annotation tags.

Figure 1

The Scheme of Predicated Themes

Data Analysis Procedure

This study compiled the data from both English and Urdu texts and developed it into a corpus. The corpus was annotated by assigning only relevant annotations tags to the data in multiple layers. The English data was annotated semi-automatically, while the Urdu data were annotated manually. After annotation, the difference in frequency of the predicated thematic structures was shown in a table. From the annotated corpus, some clauses were taken for further evaluation and discussion. The thematic progression patterns of the predicated thematic structures were also investigated, and their difference in frequency was given in a table. The patterns of thematic progression were shown on the figures to analyze their information flow.

Findings and Discussion

This study finds significant variations in the

Urdu translation of English predicated thematic structures. The variations

occur due to unmotivated displacements of

the predicated themes. Such displacements not only omit the emphasis and

contrast but also convey misleading information. Due to misleading information,

the reader of the target text misinterprets the author of the source text. This

section discusses nine cases of variations in the English and the Urdu

predicated thematic structures.

Variations in the Urdu Translation

of English Predicated Themes

The frequency of the English and the Urdu

predicated themes is investigated as follows.

Table 3. Frequency of Predicated

Thematic Structures

|

Thematic Structures |

English |

Urdu |

||

|

Predicated

Themes |

It is/was---who |

6% |

j?h he/t?h?---?o / ??s ne |

15% |

|

It is/was---which |

4% |

j?h he/t?h?---?o / ??s ke |

6% |

|

|

It is/was---that |

20% |

j?h he/t?h?---?o |

4% |

|

|

It is/was---where |

2% |

j?h he/t?h?---??h?? |

2% |

|

|

It is/was---when |

3% |

j?h he/t?h?---??b (??s me?) |

3% |

|

|

It is/was---whom |

0% |

j?h he/t?h?---??s se |

2% |

|

|

Total Frequency |

35% |

Total Frequency |

32% |

|

Analyzing the frequency enlisted in the table

(4), it is observed that some English predicated thematic structures have been

translated into Urdu marked or unmarked ideational themes. So, the English

predicated themes are more frequent than the Urdu predicated themes. But there

is not much difference between the percentage 35% of English predicated themes

and the percentage 32% of Urdu predicated themes. The following examples

selected from the source and the target texts show the unmotivated displacements

of predicated themes in the target text.

Table 4. English Predicated

Theme as Urdu Predicated Theme

|

English Text |

||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

1.1a |

|

Mr. Kiaga |

|

stood firm |

|

1.2a |

and |

|

it was his firmness |

that saved the young church. |

|

Urdu Text |

||||

|

CL |

Theme |

|

Rheme |

|

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

1.1b |

|

Mr. Kiaga |

|

s?b?t? k?d??m r?h? |

|

1.2b |

??r |

|

j?hi ?st??hk?m t?h? |

??s ne n?? ?mr g?r?e ko ?s v?qt? s?nmbh?l l?j?. |

The

English predicated theme in (1.2a) starts from it-cleft followed by a copular

verb and highlighted element firmness. The Urdu predicated theme in

(1.2b) starts from an NP as highlighted element ?st??hk?m ‘firmness’ followed by a

copular verb t?h? ‘was’. The former highlighted

element is modified by possessive adjective his while the latter is not

modified. Such difference creates ambiguity in defining contrast. The contrast

of English predicated theme specifies a man’s quality e.g. it was his firmness

while the contrast of Urdu predicated theme specifies only a quality e.g. j?hi ?st??hk?m ‘this firmness’. The writer emphasizes the firmness of a person in the English

predicated theme (1.2a) while the translator emphasizes only a specific kind of

firmness in the Urdu predicated theme (1.2b). This analysis does not show an

unmotivated displacement of the whole predicated theme. But only possessive

adjective his has been displaced and omitted in the Urdu translation.

For this English predicated theme, the possible Urdu translation choices are: j?h ?ska ?st??hk?m hi t?h? 'it was his firmness,' or ?ska ?st??hk?m hi t?h? 'his firmness was .'The variation between the predicated themes (1.2a) and (1.2b)

affects thematic progression (cf. Figure 2). The following variation highlights that the English predicated

theme has been translated as a marked ideational theme (see Table 5).

Table 5. English Predicated Theme as Urdu Marked (Complement)

Ideational Theme

|

English Text |

||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

2.1a |

|

He |

|

was called the Cat |

|

2.2a |

because |

his back |

|

would never touch the earth |

|

2.3a |

and |

|

it was this man |

that Okonkwo threw in a fight. |

|

Urdu Text |

||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

2.1b |

|

?se |

|

b?l? ?s l?je k?h? ??t?? he |

|

2.2b |

ke |

?sk? pith |

|

k?bhi z?min p?r n?hi l?gi t?hi |

|

2.3b |

|

?s x?s ko |

|

Okonkwo ne k??t?i me? ??t? k?j?. |

This

analysis exhibits that the English predicated theme in (2.3a) has been

translated as Urdu marked ideational theme in (2.3b). The Urdu thematic

structure in (2.3b) includes a complement ?s x?s ko ‘this man’ at clause initial

position. This marked ideational theme displaces the topical theme Okonkwo

which does not receive the progression of preceding themes. The translator has

placed complement at thematic prominence in order to highlight it an important

element. But this translation choice is misleading for readers because they

cannot identify the sense of exclusiveness. They may assume that there are also

other men whom Okonkwo has thrown in a fight. The English predicated theme

(2.3a) can have another translation choice e.g. j?hi vo x?s he ??se Okonkwo ne k??t?i me? ??t? k?j?. The translated theme in (2.3b) affects the

mapping of information focus. The English theme in (2.3a) involves thematic

predication in which highlighted element is an information focus. But it is not

found in the Urdu translation. Here both themes deal with constant thematic

progression despite having different information focus (cf. Figure 3). The

absence of predicated theme in the translated Urdu clause is also observed (see

Table 6).

Table 6. English Predicated Theme as Urdu Unmarked Ideational Theme

|

English Text |

|||||

|

CL |

Adjunct |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Modal |

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

3.1a |

|

|

Ezinma |

|

was an only child |

|

3.2a |

|

and |

(she) =elliptical |

|

(was) the centre of her mother's world |

|

3.3a |

very often |

|

|

it was Ezinma |

who decided what food her mother should

prepare |

|

Urdu Text |

|||||

|

CL |

Adjunct |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Modal |

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

3.1b |

|

|

Ez?nm? |

|

?klot?i b??i t?hi |

|

3.2b |

|

??r |

(vo) =elliptical |

|

?pni m?? ki d??nj? k? m?rk?z (t?hi). |

|

3.3b |

?ks?r |

|

Ez?nm? |

|

fesl? k?rt?i ke ?s ki m?? kons? kh?n? t??j?r k?re |

This analysis specifies that

the translated Urdu theme in (3.3b) is a simple unmarked ideational theme Ez?nm? without

any emphasis. This theme is not contrastive and gives the information that

Ezinma and any other persons can decide for what food to be prepared. On the

contrary, the English predicated theme in (3.3a) signifies that it is only

Ezinma who decides about the food. This difference justifies that English

predicated theme is an information focus but Urdu theme is not an information

focus. To maintain Urdu predicated thematic focus, the English predicated theme

can have an appropriate translation choice e.g. j?h Ezinma hi t?hi ‘It was Ezinma’. However, despite of different

information focus, both the English predicated theme and the Urdu unmarked

ideational theme correspond to their preceding themes and implicate constant

thematic progression (cf. Figure 4). The next analysis shows how the Urdu

translation fails to maintain the information focus, contrast and information

flow (see Table 7).

Table 7. English Predicated Theme as

Urdu Unmarked Ideational Theme

|

English

Text |

||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

4.1a |

but |

there |

|

was a

young lad who had been captivated |

|

4.2a |

|

his

name |

|

was

Nwoye, Okonkwo's first son |

|

4.3a |

|

|

it was

not the mad logic of the Trinity |

that

captivated him. |

|

Urdu Text |

||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

4.1b |

lek?n |

v?h?? |

|

ek n????v?n l??k? es? t?h? ?o ?ske se??r me? ? ??k? t?h? |

|

4.2b |

|

vo |

|

Nwoye,

Okonkwo k? p?hlothi k? bet? t?h? |

|

4.3b |

|

t??slis ki m??nun?ni m?nt?q ne |

|

?se m?t??s?r n?hi k?j? t?h?. |

The English predicated theme in (4.3a) converts

into the Urdu unmarked ideational theme in (4.3b). Both the English and the

Urdu clauses are negative but they discuss negation in different ways. The

English predicated theme in (4.3a) includes highlighted element that is negated

by the word not right after copular verb. It means that a person has not

been captivated by the mad logic of the Trinity but by something else. On the

contrary, the translated Urdu theme conveys merely an information without any

emphasis. The rheme of Urdu clause discusses negation in the sense that the

person has been captivated neither by the mad logic of the Trinity nor by

anything else. The translation choice e.g. j?h t??slis ki m??nun?ni m?nt?q nehi t?hi ??s ne ?se m?t??s?r k?j? can be selected for the English predicated thematic structure in

(4.3a). Moreover,

the English predicated theme and the Urdu unmarked ideational theme incorporate

different peripheral themes (cf. Figure 5). The succeeding analysis how the

English predicated theme has been translated as the Urdu displaced topical

theme (see Table 8).

Table 8. English Predicated Theme as Urdu Displaced Topical Theme

|

English Text |

||||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||||

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||||

|

5.1a |

but |

there |

|

were many others who saw the situation

differently |

||

|

5.2a |

and |

|

it was their counsel |

that prevailed in the end. |

||

|

Urdu Text |

||||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||||

|

Textual |

Adjunct |

Ideational |

Displaced |

|||

|

5.1b |

l?k?n |

|

v?h?? p?r |

|

boh?t? se

ese bhi t?he ?o sur?t? e h?l ko m?kht??l?f ?nd??z se ??n??t?e t?he |

|

|

5.2b |

??r |

?kh?r k?r |

|

?nhi ki r?e |

s?b p?r ??vi r?hi. |

|

The

English predicated theme in (5.2a) has been translated as the Urdu displaced

topical theme in (5.2b). The emphatic particle emphasizes displaced theme to

show contrast e.g. ?nhi ki r?e ‘only their opinion not of someone else’ but it

not a predicated theme. The English predicated theme indicates an information

focus while the Urdu displaced theme does not indicate any information focus.

To some extent, both themes deal with linear thematic progression. As the rheme

in (5.1a) shares information with the following English predicated theme.

Similarly, the rheme in (5.1b) shares information with its following Urdu

displaced topical theme. But due to the displaced theme, the adjunct at Urdu

clause initial position also denotes peripheral theme (cf. Figure 6). Moreover,

the Urdu displaced theme has failed to maintain information focus and contrast.

The translation choice e.g. j?h ?nhi ki r?e t?hi ?o s?b p?r ??vi r?hi ‘it was their counsel that

prevailed’ can be appropriate for the English predicated thematic

structure in (5.2a). The absence of information focus, contrast and

information flow in the translated Urdu theme is also observed in the next

examples (see Table 9).

Table 9. English Predicated Theme as

Urdu Rheme

|

English Text |

|||||

|

CL |

Adjunct |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Modal |

Ideational |

Predicated |

Displaced |

||

|

6.1a |

|

|

|

he |

began to speak, quietly and deliberately,

picking his words with great care |

|

6.2a |

|

|

it is Okonkwo |

|

that I primarily wish to speak to |

|

6.3a |

|

he |

|

|

began |

|

Urdu Text |

|||||

|

CL |

Adjunct |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Modal |

Ideational |

Predicated |

Displaced |

||

|

6.1b |

|

|

|

vo |

?h?st??gi se so? so? k?r ??r b??i e?t??j?t se ?lf?z k? ?nt?eh?b k?rt?e hue

bolne l?g? |

|

6.2b |

|

?sne |

|

|

b?t? ??ru ki, |

|

6.3b |

p?hle p?hle t?o |

|

|

me? |

“Okonkwo se b?t? k?rn? ??ht?? hu?” |

This description reveals that the English

predicated theme in (6.2a) has been translated as the Urdu rheme in (6.3b). The

translated Urdu theme does not include emphasis. The information focus in

English predicated theme is Okonkwo which becomes the part of the Urdu

rheme in (6.3b). The English predicated theme shows peripheral theme which is

not found in the Urdu translation (cf. Figure 7). The modal adjunct primarily

is placed in the English rheme but the translator has created ambiguity by

placing this modal adjunct at the start of Urdu clause. The whole Urdu clause

conveys misleading information. The suitable translation choice e.g. Okonkwo

hi he ??s se me? p?hle b?t? k?rn? ??ht?? hu? can be used to avoid ambiguity. This analysis shows how the

translator has translated and shifted the English predicated theme into the

Urdu rheme. He has also shifted the adjunct in English rheme at Urdu clause

initial position. Moreover, the pronoun I in the English rheme has been

translated as the Urdu displaced theme. The information focus and contrast of

the translated Urdu theme are also different (see Table 10).

Table 10. English Predicated Theme as

Urdu Marked (Adjunct) Ideational Theme

|

English Text |

||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

7.1a |

when |

the men |

|

were left alone |

|

7.2a |

|

they |

|

found no words to speak to one another |

|

7.3a |

|

|

it was only on the third day |

when they could no longer bear the hunger and

the insults, |

|

7.4a |

that |

they |

|

began to talk about giving in |

|

Urdu Text |

||||

|

CL |

Theme |

Rheme |

||

|

Textual |

Ideational |

Predicated |

||

|

7.1b |

??b |

vo log |

|

t??nh? hot?e |

|

7.2b |

t??b bhi |

?nko |

|

?p?s me? g?ft??gu ke l?je ?lf?z n? m?lt?e |

|

7.3b |

|

t??sre d?n ?? k?r |

|

??b ?n me? bhuk

??r be?z?ti b?rd???t? k?rne k? m?zid? j?r? n? r?h? |

|

7.4b |

t?o |

?nho? ne |

|

h?r m?n?ne ke

b?re me? b?t?e? ??ru ki? |

The

English predicated theme in (7.3a) is the composition of it-cleft, copular verb

and adverbial phrase. The translated Urdu theme in (7.3b) is marked ideational

theme without emphasis. The Urdu theme t??sre d?n ?? k?r ‘on the third day’ means that they tried to talk on first and

second days as well and now on the third day they began to talk. On the

contrary, the English predicated theme carrying emphasis means that not on any

other day but only on third day, they began to talk. The absence of emphasis has

affected the meanings and information flow of the translated Urdu theme. The

English predicated theme and the Urdu marked ideational theme are placed as

peripheral themes (cf. Figure 8). The translation choice e.g. j?h s?rf t??sr? hi d?n t?h? ??b ?n me?

bhuk ??r be?z?ti b?rd???t? k?rne k? m?zid? j?r? n? r?h? can have an appropriate information focus and

contrast.

The

following section analyzes the effects of

unmotivated displacements of translated themes

on thematic progression.

Thematic Progression in English and Urdu

The information structure of marked predicated

themes is defined by the thematic progression patterns (McCabe, 1999). This study identifies the

thematic progression patterns of predicated themes in the English text and its

Urdu translation. In this section, the figures highlight seven English

predicated themes and their Urdu translation. There is observed unmotivated

displacements of the translated Urdu themes. In some cases, the unmotivated

displacements of themes have affected thematic progression. But in other cases,

such displacements have not affected thematic progression and maintain

information flow. The frequency of the thematic patterns has been observed in

the following table.

Table 11. Thematic Progression of the Predicated

Themes

|

Thematic Structures |

Thematic Progression |

Peripheral Theme |

||||

|

Linear

Theme |

Constant

Theme |

Split

Theme |

Split

Rheme |

|||

|

English |

Predicated Themes |

12% |

8% |

0% |

0% |

13% |

|

Urdu |

Predicated Themes |

10% |

7% |

0% |

0% |

13% |

The

thematic progression of both English and Urdu predicated themes is equal to a

greater extent. In both source and target texts, the predicated themes are

mostly observed at periphery position. The linear themes are more than the

constant themes. Consider the following figures showing thematic progression.

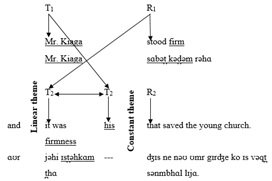

Figure 2

Predicated Theme with Linear and Constant Thematic Progression

This figure indicates a combination of linear and constant thematic progression in the English predicated theme. Such combination of two main patterns of thematic progression is unique. The translated predicated theme contains only linear thematic progression. In English predicated theme, the possessive adjective his connects to the preceding theme Mr. Kiaga and maintains a constant information flow. The nominal firmness connects to its preceding rheme firm and maintains linear information flow. In the Urdu predicated theme, the possessive adjective is omitted and only the nominal ?st??hk?m ‘firmness’ connects to the preceding rheme s?b?t? k?d??m ‘firm’ and maintains linear thematic progression. This variation in Urdu translation of predicated theme affects information focus, contrast and information flow. But the variation in Urdu translation has no effect on information flow in the following analysis.

Figure 3

Constant Progression in English Predicated and Urdu Marked Ideational Themes

This figure shows that the English and the Urdu predicated themes contains constant thematic progression. The English predicated theme this man and the translated Urdu theme ?s x?s ‘this man’ receive information from the preceding themes i.e. pronominal and possessive adjective. The translated Urdu theme maintains the identical thematic progression but being a complement ideational theme, it loses information focus and contrast. The constant thematic progression is also observed in the following analysis.

Figure 4

Constant Thematic Progression in English Predicated and Urdu Unmarked Ideational Themes

This figure highlights that the English predicated theme and the translated Urdu theme receive information from the preceding theme T1 and maintain constant thematic progression. The translated Urdu theme is an unmarked ideational theme so, it fails to maintain the information focus and contrast. The next Urdu translation fails to maintain not only information focus and contrast but also information flow.

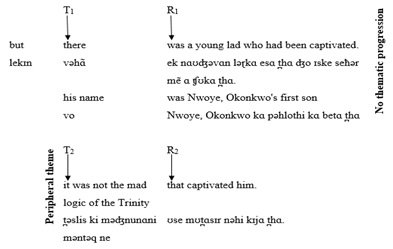

Figure 5

English Predicated and Urdu Unmarked Ideational Themes as Peripheral Themes

This figure shows no thematic progression in the English predicated theme and the translated Urdu theme. Both themes are located at periphery position. The translated Urdu theme is an unmarked ideational theme which loses information focus and contrast of English predicated theme. The next English predicated theme consists of two types of thematic progression.

Figure 6

Linear Thematic Progression in English Predicated and Urdu Displaced Topical Themes

This figure shows that the English predicated theme and the translated Urdu theme have linear thematic progression. Besides, the English predicated theme and the translated Urdu theme are also located at periphery position. There is also accommodated an extra adjunct at periphery position. Moreover, the Urdu translated theme is a displaced theme so, it does not maintain information focus and contrast. The following analysis shows that the English and the Urdu themes have different patterns of thematic progression.

Figure 7

Peripheral Theme in English and Constant Thematic Progression in Urdu

This figure indicates that the English predicated theme has been translated as Urdu rheme Okonkwo. This unmotivated displacement of the translated Urdu theme affects thematic progression and causes misleading information. In this figure, the Urdu theme T1 continues to be selected as the Urdu theme T2 showing constant thematic progression. But the English predicated theme T2 is placed at periphery position and does not connects its information to the preceding theme. Due to these variations, the Urdu translation fails to maintain information focus, contrast and information flow. In the next analysis, the English predicated theme and the translated Urdu theme T2 are located at periphery position.

Figure 8

English Predicated and Urdu Marked Ideational Themes as Peripheral Themes

This figure shows that the English predicated theme translated as the Urdu marked ideational theme can have identical information flow but cannot have identical information focus and contrast. The English predicated theme and the translated Urdu theme T2 are placed as peripheral themes. But the information of R2 flows down in the theme T3showing linear thematic progression. In this analysis, the unmotivated displacement of the translated Urdu theme does not affect information flow.

Conclusion

This study has addressed the research questions by analyzing the Urdu translation of English predicated thematic structures and their thematic progression. Through the contrastive analysis of both texts, it is concluded that the author of English text incorporates the predicated theme to emphasize the most important and certain aspects of information. The translator of Urdu text also applies emphasis on the most required information but mostly he has used ambiguous and misleading translation choices. Most of the English predicated themes are not translated as the Urdu predicated themes. It is also concluded that the Urdu translation shows some unmotivated displacements of themes. Due to the unmotivated displacements, the translated Urdu themes are unable to preserve the information focus and contrast. The unmotivated displacements of the translated Urdu themes have also affected thematic progression. The predicated theme is always a marked theme carrying new information (Halliday 1985). But this study finds that besides the new information, the marked predicated theme also carries constant and linear thematic progression.

This study has found the following variations in the Urdu translation of the English predicated themes. Firstly, some English predicated themes have been translated as Urdu predicated themes with different information focus, contrast and thematic progression. Secondly, some English predicated themes have been translated as Urdu marked (complement or adjunct) ideational themes with different information focus and contrast but with similar thematic progression. Thirdly, some English predicated themes have been translated as Urdu unmarked ideational themes with different information focus and contrast but with similar thematic progression. Lastly, some English predicated themes have been translated as the rhemes of Urdu clauses with different information focus, contrast and information flow. Analyzing these variations, the researcher has suggested the appropriate translations choices according to the Urdu predicative formula. This study suggests that the translators of the target texts should be careful in translating the thematic structures of the source texts.

References

- Achebe, C. (1958). Things fall apart. London: Heinemann.

- Baker, M. (1992). In other words: A coursebook on translation. London: Routledge.

- Butt, D. et al. (2000). Using functional grammar: An explorer's guide. Sydney: Macquarie University

- Butt, M., & King, T. H. (2005). The status of case. In Veneeta Dayal & Anoop Mahajan (eds.), Clause structure in South Asian languages, 153-198. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Butt, M., & King, T. H. (2007). Urdu in a parallel grammar development environment. Language Resources and Evaluation 41(2). 191-207.

- Collins, P. (1991). Cleft and pseudo-cleft constructions in English. London: Routledge.

- Danes, F. (1974). Functional sentence perspective and the organization of the text. In Frantisek Danes (ed.), Papers on functional sentence perspective. 106-128. Prague: Academia /The Hague: Mouton.

- Downing, A. (2001). The theme-topic interface: Evidence from English. Amsterdam:Lohnnswert.

- Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. New York: Continuum

- Erdmann, P. (1990). Discourse and grammar: Focussing and defocussing in English. Tiibingen: Newmeyer.

- Grabe, W., & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Theory of practice of writing: An appliedlinguistic perspective. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Halliday, M. (1967). Notes on transitivity and theme in English. Journal of Linguistics 3.199-244.

- Halliday, M. (1985). An introduction to functional grammar. London: Edward Arnold

- Halliday, M. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar. London: Edward Arnold

- Halliday, M., & Matthiessen, C. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar. London:Hodder Arnold.

- Hasan, R. (1984). Ways of saying, ways of meaning. In Robin P. Fawcett, Michael Halliday, Sydney Lamb & Adam Makkai (eds.), The semiotics of language andculture volume1: Language as social semiotic. London: Francis Pinter

- Huddleston, R. (1984). Introduction to the grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Johansson, M. (2002). Clefts in contrast: A contrastive study of it clefts and wh clefts in English and Swedish texts and translations. Linguistics 39(3), 547-582.

- Katz, S. (2000). A functional approach to the teaching of the French c'est-cleft. French Review 74, 248-262.

- Kuswoyo, H. (2016). Thematic structure in Barack Obama's press conference: A systemic functional grammar study. Advances in Language and Literary Studies 7(2). Australian International Academic Centre, Australia.

- Lavid, J. (2010). Contrasting choices in clause- initial position in English and Spanish: Acorpus-based analysis. In Elizabeth Swain (ed.), Thresholds and potentialities ofsystemic functional linguistics: Multilingual, multimodal and other specializeddis courses. 49-68. Trieste: EUT

- Lavid, J., Arús, J., & Moratón, L. (2010a). Annotating thematic features in English and Spanish. In Maite Taboada, Susana Doval Suárez & Elsa González Ãlvarez (eds.),Contrastive discourse analysis. London, England: Equinox. 22, 94, 134.

Cite this article

-

APA : Yaqub, H., Ahsan, A., & Iqbal, M. (2021). A Contrastive Analysis of Predicated Thematic Structures in the English Novel and its Urdu Translation. Global Social Sciences Review, VI(IV), 144-160. https://doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2021(VI-IV).14

-

CHICAGO : Yaqub, Humaira, Ansa Ahsan, and Mubashir Iqbal. 2021. "A Contrastive Analysis of Predicated Thematic Structures in the English Novel and its Urdu Translation." Global Social Sciences Review, VI (IV): 144-160 doi: 10.31703/gssr.2021(VI-IV).14

-

HARVARD : YAQUB, H., AHSAN, A. & IQBAL, M. 2021. A Contrastive Analysis of Predicated Thematic Structures in the English Novel and its Urdu Translation. Global Social Sciences Review, VI, 144-160.

-

MHRA : Yaqub, Humaira, Ansa Ahsan, and Mubashir Iqbal. 2021. "A Contrastive Analysis of Predicated Thematic Structures in the English Novel and its Urdu Translation." Global Social Sciences Review, VI: 144-160

-

MLA : Yaqub, Humaira, Ansa Ahsan, and Mubashir Iqbal. "A Contrastive Analysis of Predicated Thematic Structures in the English Novel and its Urdu Translation." Global Social Sciences Review, VI.IV (2021): 144-160 Print.

-

OXFORD : Yaqub, Humaira, Ahsan, Ansa, and Iqbal, Mubashir (2021), "A Contrastive Analysis of Predicated Thematic Structures in the English Novel and its Urdu Translation", Global Social Sciences Review, VI (IV), 144-160

-

TURABIAN : Yaqub, Humaira, Ansa Ahsan, and Mubashir Iqbal. "A Contrastive Analysis of Predicated Thematic Structures in the English Novel and its Urdu Translation." Global Social Sciences Review VI, no. IV (2021): 144-160. https://doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2021(VI-IV).14